Investigating the waste in our cells: So that we can soon forget about Alzheimer’s

17. February 2022

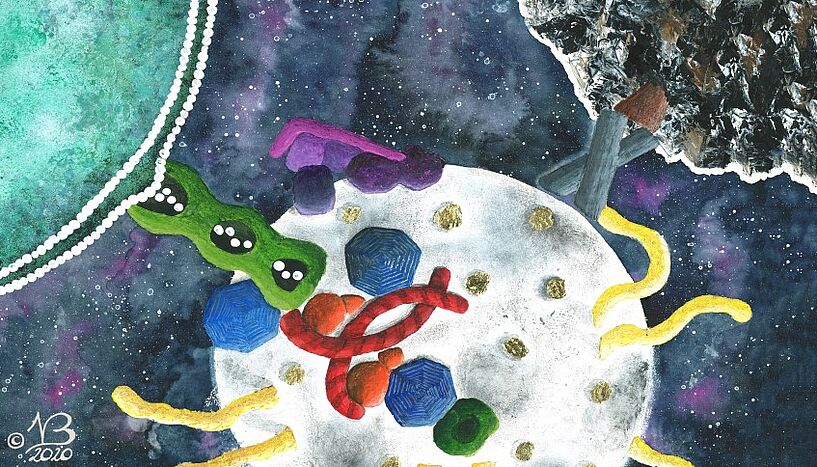

An Atg9 vesicle serves as a platform for the recruitment of the autophagic machinery. It thereby forms a seed for the formation of an autophagosome around the cargo by accepting lipids that are transferred by the Atg2 protein from the neighbouring endoplasmic reticulum (ER). (© Verena Baumann)

Autophagy: What to do with the waste in our cells?

A 'waste collection' tidies up our cells. If something does not go according to plan, serious diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson's may develop. Molecular biologist Sascha Martens from the University of Vienna together with international partners – researchers of the University of Pennsylvania, Monash University, the Max Planck Institute of Biophysics in Frankfurt and the UC Berkeley – investigate the associated process: autophagy. Martens and his team have recently published new results on these mechanisms in Nature Communications and The Journal of Biological Chemistry.

With investigating a tiny mechanism happening every millisecond in every single one of our body cells, an international team of researchers is helping to create the foundations for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. The key process that the scientists investigate in this context is the cellular waste disposal system. After all, also our cells produce 'waste' all the time.

Autophagy: What to do with the waste in our cells?

An elaborate molecular surveillance force identifies suspicious substances – broken cell components, coagulated proteins or pathogens – and initiates their removal: They are packed in a 'bag' (a double membrane that enwraps the waste) and brought to the cell's 'recycling bin' (the lysosome). There, the damaged cell components are decomposed and recycled. This self-cleaning process of the cell is called autophagy, which is Greek for 'self-devouring'. "And it is a perfectly running, self-organised machinery," says Sascha Martens, molecular biologist and leader of the sub team at the University of Vienna. He and colleagues want to understand in detail how molecules cooperate in the production of the autophagosomes because this is where diseases, ranging from infections to neurodegenerative diseases, can originate.

Hunting Alzheimer’s and Parkinson's

Alzheimer’s often develops in our bodies for decades without being noticed, until the first symptoms show and the disease can be finally diagnosed. The tau protein is strongly suspected of causing the most common form of dementia worldwide. The protein forms elongated aggregations in our neural cells. These aggregates are usually detected and degraded by the autophagy machinery. This is very similar to Parkinson’s, the second disease that Martens' team investigates in relation to the cellular waste disposal system.

Parkinson's is one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases. Here, an error occurs in the disposal of damaged mitochondria – the energy suppliers in our cells – in a specific part of the brain that is responsible for releasing the chemical messenger dopamine. In the long term, this causes the typical symptoms of Parkinson's: Patients can no longer control their movements, muscles stiffen and tremble also at rest.

Joining forces

Researchers from the University of Vienna, the University of Pennsylvania, Monash University, the Max Planck Institute of Biophysics in Frankfurt and the UC Berkeley decided to join forces to investigate Parkinson's at the cellular level. For their recent project, they received more than 7 million dollars of funding provided by the Initiative Aligning Science Across Parkinson's (ASAP), a research network that cooperates, among others, with the The Michael J. Fox Foundation.

"You could compare it to a band: Some are excellent on guitar and bass, others are drummers or convince with their vocals. But the song can only be perfect when being played together," Sascha Martens is convinced. The experts on protein structures are based in the "Hurley Lab" at UC Berkeley, the manipulation of cells happens at the Monash University around Michael Lazarou, the team of Erika Holzbaur at the University of Pennsylvania is one step ahead in neurobiology and the researchers under the lead of Gerhard Hummer at the Max Planck Institute of Biophysics are preparing models. Sascha Martens and his team at the University of Vienna have specialised on reconstituting the autophagy machinery in the laboratory.

Decipher the next central steps

Several proteins are involved in the process of autophagy. In more than ten years of tedious research, Sascha Martens and his dedicated team have managed to isolate dozens of these components and have been able to recapitulate the early steps in the formation of the autophagosome. Following the modular principle, they now want to decipher the next central steps in this clever machinery that tidies up our cells.

CV Box Sascha Martens: After working at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, Sascha Martens came to the University of Vienna in 2009 to investigate the mechanisms of autophagy in the model organism yeast and in human cells. Sascha Martens is now surrounded by a team of 12 international researchers and has received two ERC grants for his research endeavour.

Recent publications:

The Journal of biological chemistry: Mechanism of Atg9 recruitment by Atg11 in the cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting pathway

In this publication the team has shown how the initial seeds for the membrane that will engulf the waste are brought to it.

Nature Communications: Reconstitution defines the roles of p62, NBR1 and TAX1BP1 in ubiquitin condensate formation and autophagy initiation

In this publication the team discovered how several molecules work together to accumulate the waste in larger particles, such that is can be efficiently wrapped up and disposed of by the autophagy machinery.

Pictures:

Pic. 1: An Atg9 vesicle serves as a platform for the recruitment of the autophagic machinery. It thereby forms a seed for the formation of an autophagosome around the cargo by accepting lipids that are transferred by the Atg2 protein from the neighbouring endoplasmic reticulum (ER). (© Verena Baumann)

Pic. 2: Sascha Martens (© feelimage / Matern)

Scientific contact

Univ.-Prof. Dipl.-Biol. Dr. Sascha Martens, Privatdoz.

Department für Biochemie und ZellbiologieUniversität Wien

1030 - Wien, Dr.-Bohr-Gasse 9

+43-1-4277-528 76

+43-664-60277-528 76

sascha.martens@univie.ac.at

Further inquiry

Mag. Alexandra Frey

Media Relations ManagerUniversität Wien

1010 - Wien, Universitätsring 1

+43-1-4277-17533

+43-664-8175675

alexandra.frey@univie.ac.at

Downloads:

Pic1_20220217_Martens.jpg

File size: 3,38 MB

Pic2_20220217_Martens.jpg

File size: 230,82 KB