Chemistry: From the jungle to the clinic

| 10. Januar 2018Deep in the jungle, two researchers go on a hunt. What sounds like an adventurous trip, is part of Markus Muttenthaler’s research at the Faculty of Chemistry. The ERC Starting Grant holder is looking for new therapeutic strategies to combat gastrointestinal diseases based on natural substances.

About ten to 15 percent of the Western population is affected by chronic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Inflammatory bowel disease or irritable bowel syndrome are the reason for many people’s misery. As for now, treatment options are limited. That's exactly what ERC Starting Grant recipient Markus Muttenthaler wants to change. At the Institute of Biological Chemistry of the University of Vienna, he is developing new therapeutic strategies based on natural substances.

"Many gastrointestinal disorders derive from a damaged, inflamed or leaky gut barrier, which over time results in chronic conditions. We are therefore interested in novel mechanisms to protect or rapidly repair the gut barrier," Muttenthaler explains and adds, "Rather than targeting the underlying causes, most current treatments only deal with the symptoms of the disease." In addition to treating chronic bowel diseases, the strategies developed by Muttenthaler and his team could also be used for gut protection during chemotherapy or as protective agents for patients who regularly take medication that damages the gut barrier in the long term.

From the jungle…

The greatest challenge is to find bioactive substances that can ultimately be useful for human therapy. Muttenthaler and his team focus on venom compounds since they interact with mammalian receptors with incredible potency and selectivity: "Since animal receptors are structurally similar to human receptors, many of these compounds are also active in humans, where they could be used therapeutically," Muttenthaler explains.

The first part of the preclinical development aims at acquiring these substances. Venoms of animals, such as spiders, scorpions or snakes, comprise hundreds to thousands of active compounds and every animal has its own special mix. However, they are not easy to come by, since most venomous animals don't have their habitat in cities – unless you live in Australia. Instead, the researchers need to travel to faraway places like the Great Barrier Reef or the Amazonian jungle. When it gets dark, Muttenthaler and his team go on a hunt. Deep in the jungle, they look for venomous spiders.

…to the clinic?

The beauty about chemistry is that you can make identical copies of natural substances, but at much larger scale. "Animals had often millions of years to optimise their venom against prey and predators," Muttenthaler explains. Back from their hunting trip, they collect the venom and test it against a panel of receptors that have been associated with diseases such as pain, cancer or inflammation. Once they have a hit, they synthesise the active molecule and characterise it further.

"If a synthesised compound holds up, we use Medicinal Chemistry to optimise the lead, so that it stays stable in the human body and actually reaches its target organ," Muttenthaler explains the process. His great hope is to develop therapeutic lead compounds that could ultimately be moved forward to the clinic.

Developing drugs based on natural substances is not unusual. On the contrary, many well-known drugs derive from natural substances: morphine derived from the flowering poppy plant, aspirin from the bark of the willow tree. A more recent example is the peptide drug Prialt, which is produced from the venom of the cone snail. The snail uses it to paralyse fish, but in humans Prialt can treat severe chronic pain.

Reducing chronic pain

But not only venoms play a significant role in Muttenthaler’s research: Oxytocin, the so-called "love hormone", is another piece of the puzzle of developing new therapeutic approaches. Oxytocin is mainly known for its function of mother-child bonding and love, but it is also present in the gut. "We have recently shown that people suffering from chronic abdominal pain also have increased levels of oxytocin receptors, and now we are interested in studying this observation further," says Muttenthaler.

After living in Australia and California for almost ten years, Muttenthaler returned to Austria to – as he puts it – establish himself in Vienna, at the Faculty of Chemistry: "Thanks to the ERC Starting Grant, I am now able to set up operations and expand and strengthen my research direction." (pp)

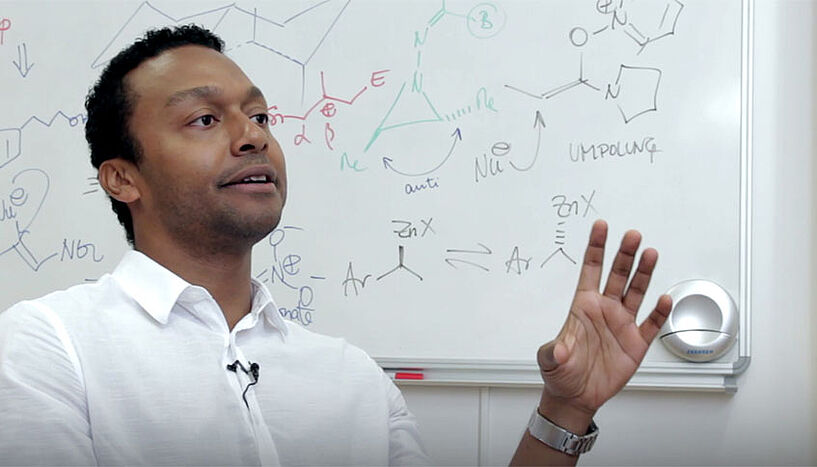

Markus Muttenthaler, Group Leader of the Neuropeptide Research Lab at the Institute of Biological Chemistry. His interests lie in the exploration of nature's diversity to develop molecular tools, diagnostics and therapeutics. His background in drug discovery, design and development helps him in the characterisation of these compounds and allows him to study their interactions with human physiology. (Foto: Anjanette Webb, Capture Studio).

In 2017 the biochemist Ass.-Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Markus Muttenthaler, PhD received the renowned ERC Starting Grant. In his ERC project he looks for new therapeutic strategies to combat gastrointestinal diseases based on natural substances. 43 ERC Grants have already been awarded to researchers of the University of Vienna since 2007.