"A green world needs long-term climate policies"

| 10. Mai 2021Humankind faces its most severe crisis in the 21th century. Economist Alexandra Brausmann from the University of Vienna explains how the climate crisis affects the economy and why a different emission trading system is needed.

uni:view: In your papers, you write about "environmental shock". What exactly does this mean?

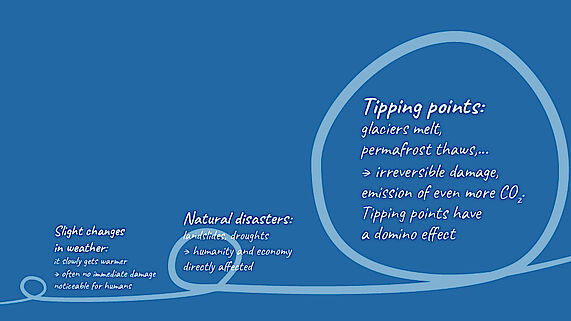

Alexandra Brausmann: In environmental economics, we typically distinguish between three types of environmental shocks. The unpredictability or uncertainty surrounding these shocks is a major problem. The first type are the so-called micro-shocks, or short-term fluctuations, which are the least severe ones: This can be a slight change in weather patterns, for instance, change in the onset of the rainy season or short-term temperature fluctuations. These events do not cause severe damages to the economy but they are still undesirable as long as we cannot predict them with certainty.

The next type of shock – and this can be natural disasters such as landslides, flooding or disease – damages the economy and the infrastructure severely: Human lives are in danger, but also productive capacity compacity, loss of roads, machines – anything fits here. These disasters decrease the gross domestic product up to five percent or so. It has been documented, by IPCC (2014) for example, that the frequency and severity of these disasters has risen drastically, not to say exponentially, over the last three decades. But what is worse is that poorer regions of the world are more frequently affected by these disasters. Therefore, we can conclude that inequality may potentially increase over the course of time if appropriate mitigation and adaptation measures are not taken promptly.

Environmental economists distinguish between three types of ecological shocks. While slight weather changes are hardly visible, tipping points clearly show the devastating extent of the climate crisis: All habitats are endangered - including those of humans. (©University of Vienna, M. Bauer)

uni:view: And there is another type of disasters with large-scale consequences?

Brausmann: Yes – disasters of a scale of which not everybody is aware. In economics and natural sciences, these catastrophes are called tipping points. When a system reaches a certain threshold, it either collapses, or the way it functions changes completely. The truth is that right now, we are actually facing this risk of running into a tipping point: Losing the Greenland ice sheet or the destruction of the Amazon rainforest are only two examples. It is especially worrisome because once a tipping point is passed, the situation is irreversible: When the ice sheet is gone, there is no way to rebuild it. These severe disasters are not only damaging per se, but they could also trigger a chain of disasters, since everything is interconnected.

uni:view: Which policies are needed to combat the climate crisis?

Brausmann: In order to avoid the environmental crisis, we need to implement stringent climate policies that lead to a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. In theory, there are two models that can lead to such a reduction: a carbon tax or an emission trading system. If you want to limit the quantity of emissions, you are better off with an emission trading system, because there would be an allowed maximum defined by the authorities. The quantity is fixed, the price is variable. When we talk about the carbon tax it is the other way round: The price is fixed and economic agents decide how much they are going to pollute.

In this particular setting, we should not forget that our mitigation policy is related to economic growth and vice versa. To some extent, this point has been neglected by economists until now. And even now, many economists still look at these two developments as completely isolated processes, which is misleading. Our growth depends on how we behave, which resources we use, how we innovate, how much greenhouse gases we abate but our climate policy also depends on all these things and on the growth rate in particular. Everything is interconnected. But this is good news because we can, to some extent, steer our climate policy by choosing how to grow.

Alexandra Brausmann is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics at the University of Vienna. In her research, she focuses on environmental economics specialising in carbon pricing and transition to a low-carbon economy. At the moment she teaches the course Growth and Climate Change at the University of Vienna. (©Alexandra Bausmann)

uni:view: You said an emission trading system could be a possible strategy. Since this type of model already exists – it does not lower current greenhouse gas emissions?

Brausmann: The EU emissions trading system does not cover every sector. The largest polluters, such as aviation, the cement or the transportation industry, are getting the certificates for free. This is because of carbon leakage: If the European cement industry pays for its pollution, its products will become more expensive. This would mean a loss of competitiveness and buyers will switch to more cheap producers, to producers in a country without regulated emission system. Ideally, there would be a global government which would set the policy for carbon emissions. The fundamental reason why it is hard to solve the climate problem is because the climate is a public good and unfortunately, this means free riding.

uni:view: What about carbon pricing?

Brausmann: The problem with carbon taxes is that the social cost of carbon is way too low at the moment: between 20 and 40 US dollars per ton CO2. Once this aspect gets connected to growth and the possibility of crossing a tipping point, the social cost of carbon is multiplied by 50 or 100. One ton of CO2 can easily reach 400 to 800 US dollars. It is easier to justify a twenty-dollar carbon tax from a political point of view. This is also one of the reasons why political actors avoid this discussion, because it is hard to tell people the real cost of global warming.

People often forget the other side of the coin: A fair-priced carbon policy is not expensive for the economy, since it leads to a so-called double dividend. The carbon tax money can be put towards other causes: For instance, to reduce other tax rates to compensate inequality and the redistribution of wealth. The need for a functioning carbon tax system has to be communicated to the public and it will pay off over time.

uni:view: Which other measures can be taken to avoid the tipping points?

Brausmann: The free riding problem will not just disappear. As citizens we can make a difference. We need to have a critical mass of people and/or countries that implement the right policies. If enough people take action, a sustainable way of living will become affordable to everybody and this is where we need to go. However, in the role of consumers and producers, by small, individual contributions the crisis cannot be fixed at all.

From an economic point of view, there are two options for significantly reducing global greenhouse gas emissions: Emissions trading or a CO2 price. Join the discussion on derStandard.at about which measure makes more sense in your opinion. (©erdgeschoss)

Education is another way of combating the crisis. A lot of people do not know about the severity of the situation we are in or simply cannot afford to take climate-friendly decisions. The latter problem applies not only to poor developing countries but also to poor people in the rich economies – think about the yellow vest protesters. A bold way of raising climate awareness is demonstrating on the streets to claim rights on climate justice. This is already happening if you think about Greta Thunberg. But we also need to be careful here because such actions may be perceived as too pushy, not everybody may like this.

uni:view: What is your personal vision of a green economy in the future?

Brausmann: If we want to live in a green world, we need to green both sides: consumption and production. Governments can guide consumer preferences by making goods which are sustainably produced more accessible. In terms of production, the use of fossil fuels has to be stopped. The industrial use of coal has to be banned. In an ideal world, all coal mines would be shut down tomorrow. These technologies should be replaced with renewable energy sources and we definitely need more green innovation. I think green economy is not only about clean technologies but most of all about a ’clean’ lifestyle. I wish we all had access to healthy foods, clean water, can exercise in the fresh air and reach a healthy work-life balance.

uni:view: Thank you for the interview. (lk)